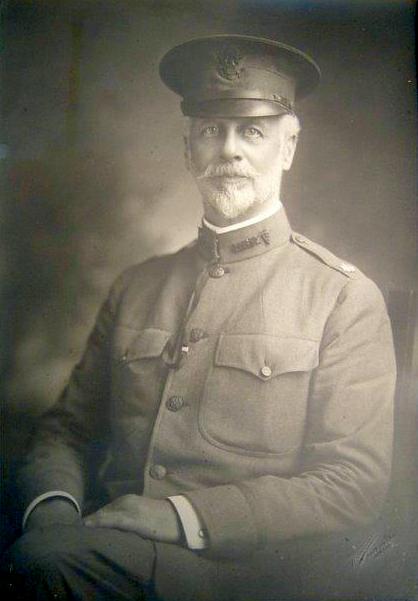

Major Graeme M. Hammond, M.D.

Dr. Graeme Monroe Hammond, the first Commander of American Legion Post 754 at the New York Athletic Club, was born in Philadelphia on February 1, 1858. His father, Dr. William Hammond was a career Army medical officer who rose to the rank of Surgeon General during the Civil War. Young Graeme spent several childhood years in Washington during the war and one of his cherished memories was accompanying his father and President Abraham Lincoln as they made their rounds visiting wounded soldiers. After the Civil War the family moved to New York City.

Graeme graduated from Columbia University’s School of Mines in 1877 and from New York University’s School of Medicine in 1881. He then pursued a residency in psychiatry, at the time referred to as “alienism”. Dr. Hammond quickly gained renown in the field, becoming a Professor of Mental and Nervous Diseases at NYU’s School of Medicine and serving as the President of the American Psychiatric Association in 1908 and as Treasurer of the New York Neurological Society, a post he held for thirty years. In the midst of his medical career, Dr. Hammond managed to find the time to attend NYU’s School of Law, from which he graduated in 1897.

Apart from his professional attainments in medicine and law, Dr. Hammond was a dedicated and lifelong athlete, one who embodied the ethos of the New York Athletic Club which he joined in 1883. He was a capable boxer and a wrestler, enjoyed rowing, running and jumping, played football, tennis, lacrosse and handball and became an enthusiastic supporter of the relatively new sport of bicycling. He carefully evaluated the kinesiology of cycling and concluded that it enhanced symmetrical physical development more than any other mechanical device available at that time. He did not enjoy golf but wryly promised that he would take up the game when he was well into his eighties.

But it was fencing that became his lifelong passion and which thrust him to the forefront of amateur athletics in America. In 1891 he was the national foil champion and in 1893 he captured the national sabre championship. He won the national title for dueling swords in 1889, 1891 and 1893. He fenced with the NYAC team and other teams and during his life he won nine amateur sports championships

He was an organizer too. He founded the Amateur Fencers League and served as its President until 1925. He organized fencing meets in the United States and overseas to popularize the sport and welcomed women into competitive fencing, even in mixed matches with men. Of the sport he would write: “There is no better sport for developing strength with suppleness and agility. Anyone who believes that a fencing lesson or a bout is a light and easy exercise should try it and become convinced of his error.” 1. His tireless promotion of fencing led to its inclusion in the Olympic Games, which brought Dr. Hammond into prominence in the early Olympic movement. At age 54 he competed at the 1912 Stockholm Olympics and was the last American eliminated from the competition placing fourth overall. He was also the physician to the American contingent to the Stockholm Games. In 1920, as President of the Amateur Fencers League in America, he selected twelve individuals for the 1920 Antwerp Olympics in which he also competed. In 1922 Dr. Hammond was Vice President of the American Olympic Association and its President from 1930 to 1932. Dr. Hammond is considered to be The Father of Fencing in America and by 1928 the medals he won over 37 years in running, jumping rowing, bicycling and fencing occupied a case at the New York Athletic Club that was five feet long and three feet wide. For his accomplishments as an amateur athlete, Dr. Hammond is in the U.S. Fencing Hall of Fame as well as the New York Athletic Club’s Hall of Fame.

As a physician trained in psychiatry as well as being an accomplished athlete, Dr. Hammond understood and promoted the health benefits of an athletic regimen. He believed regular exercise to be a chief aid to health along with rest and moderation in the consumption of food and alcohol.

Because of his legal training and professional attainments in psychiatry, Dr. Hammond served as an expert witness in a number of criminal trials and always as a witness for the defense. He was one of the three defense expert “alienist” witnesses in the 1907 trial of Harry Kendall Thaw, a wealthy Pittsburgh heir to a railroad fortune. Kendall was on trial for the murder of prominent architect Stanford White on June 25, 1906 at the restaurant atop Madison Square Garden. Thaw believed that White had trifled with the affections of his young wife, the former Evelyn Nesbit, a chorus girl, and in a rage shot White dead in the crowded restaurant. Thaw was tried twice; the first trial ended in a mistrial because of a hung jury and in the second trial Thaw was found not guilty by reason of insanity and committed to an upstate asylum for the criminally insane. He was released after four years when psychiatrists, including Dr. Graeme testified Thaw had regained his sanity and could be discharged. The trail completely captured the nation’s interest and for years was called “The Trial of the Century”.

Dr. Hammond was a committed member of the New York Athletic Club and because of his remarkable capabilities served as its President from 1916 to 1919, and was appointed to his third term by a unanimous vote of the Club’s Board of Governors.

While Dr. Hammond served as Club President, America entered World War One and so, like his father, he became an Army physician. Commissioned a Major in the Army Medical Corps, he examined over 77,000 men in Camp Upton and Spartanburg to assess their fitness for military service. Some of his conclusions were astute and, indeed, prescient. He determined that education, while useful to a soldier, was not a determinant or a predictor as to how a soldier would perform in battle. He also believed that women would make excellent soldiers and were fully capable of serving in the combat arms of the services. After the war Dr. Hammond became an expert in the treatment of “shell-shocked” soldiers. He also served on the New York Athletic Club’s Committee that selected the artist and the design for the Club’s Tiffany stained-glass World War One Memorial Window on the ninth floor of the City House and, appropriately, Dr. Hammond’s portrait hangs next to the memorial.

In 1920, shortly after the NYAC’s American Legion Post received its charter from the National Organization, Dr. Hammond was elected the Post’s first Commander, a position he held for one year. Under Dr. Hammond’s leadership, and with his knowledge of and respect for the New York Athletic Club, the Post was established on firm footing and grew steadily over the years. Today it is still one of the largest and most active posts in the Legion’s New York State Department.

Dr. Graeme never stopped participating in athletics. He ran three laps around the Club’s indoor and outdoor tracks three times a week and on his eightieth birthday he ran four laps, one for every score in his life. He passed away in his hospital at 9 PM on October 30, 1944. Dr. Graeme Hammond was eighty-six years of age and as far as can be determined there are no reports that he ever took up the game of golf.